Coal and Progress on the W&OD: Reconstructing a hidden history of a beloved trail

By Sam Libberton

This essay looks at the Washington and Old Dominion Trail, a regional park and rail trail in Northern Virginia. The fates of the railroad preceding the trail rose and fell with coal, a fact hidden from official tellings of the park’s history on informational plaques dotting the trail. I work through these silences to help contextualize this important artery of Northern Virginia.

A few miles from my house, there’s a bike trail. Stretching from the flats of the Potomac River to farmland deep in Loudoun County, the Washington and Old Dominion Trail is a park 100 feet wide and 45 miles long. A former railway, the W&OD today is a keystone of recreation in the area. Its history is important regionally, yet that history isn’t always evident.

A sunny Saturday makes for a perfect day on the W&OD. The trail is crowded. It always seems that way, even when it’s too cold, too windy, too wet to really be fun. On a warm day at the tail end of a dreary April, there were more people than I could ever remember seeing. It makes sense; plenty of Northern Virginia is bereft of parks and green space that don’t need a car to get to, and the W&OD is a lifeline. And the state hadn’t closed its parks for coronavirus, but it had closed the parking lots. For a populus stir-crazy six weeks into quarantine, the W&OD was the place to be.

When I was too young to drive, the W&OD would be my first pick to get out of the house. The W&OD—I’ve heard some people pronounce it “the wad,” but to me it’s always been the letters—was a place to get some fresh air, some space from my parents, and a little peace of mind. But I hadn’t been on it for years. With my own out of commission thanks to years of neglect, I borrowed my dad’s bike and took to the trail.

I started from the eastern end, at the bottom of the slow slope from hill country to the river, and biked west. This was the sort of ride that I’d do a couple times a week in my high school summers, looking for a way to burn off some energy. It had been a while since I’d been on my bike, though—been a while since I’d done much exercise at all, come to think of it—and this time around was different. Slower, mostly, but a little more freeing, too; I couldn’t remember the last time I’d hit the W&OD without a cycling app or heart rate monitor or some fancy tech to make sure I was going exactly as fast as I wanted to. Back then, I would’ve felt guilty taking a pit stop to enjoy the scenery and take a few pictures; that just wasn’t how I engaged with the trail. This time around, stopping gave me the chance to take in the scenery while not at speed—and a much-needed chance to catch my breath.

The W&OD, at least the Arlington leg, is verdant. There’s no other way to put it. The trail follows the old rail embankment maybe twenty feet above Four Mile Run, flanked with thickets of trees and walls of kudzu. Not all the trail is quite like that—out in Loudoun County it flits between suburban office park and McMansion subdivisions—but the Arlington leg, the leg I know best, is a little linear oasis. For a few miles, it’s easy to forget that you’re in the middle of some of the densest and oldest DC suburbs.

The trail hasn’t always been a trail. Most of the area’s residents—myself certainly included—are too young or too new to the area to remember it being anything else. The path was laid in 1979, after all, and the impact of the trail is far more obvious than what came before. But 45 mile rights-of-way through thick suburban development tend not to appear out of the blue. The W&OD is a rail trail, the last remnant of a 70-odd-mile railroad that once reached the Blue Ridge Mountains. Though the rails are long gone, the railroad’s past lingers over the trail. Though the history of the railway and the trail doesn’t always make itself overt, recalling it helps us better understand how the trail came to be the key piece of green space it is today.

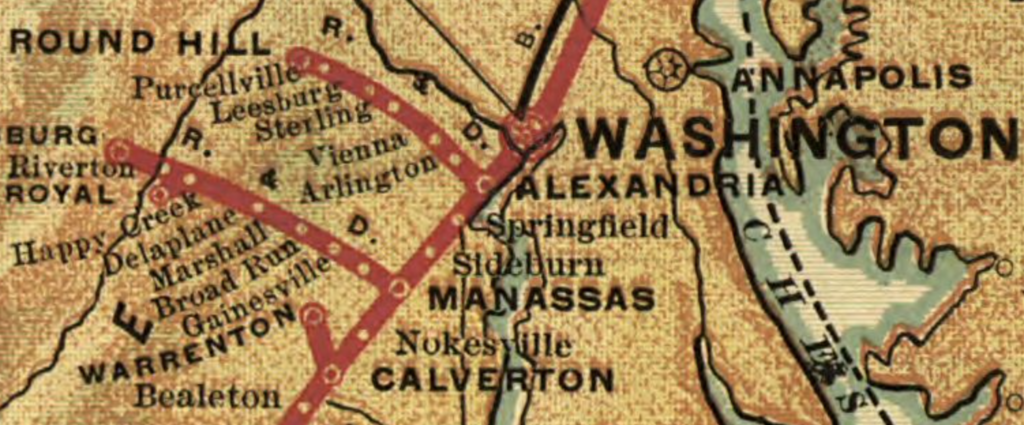

The first rails were laid along the route in 1855. Lewis McKenzie, an Alexandria politician and merchant, saw the nascent coal boom in western Virginia—now West Virginia—as a prime investment opportunity. The railroad that became the W&OD was first chartered as the Alexandria, Loudoun, and Hampshire, an intrastate line from the Potomac shores to western coal fields.(1) Alexandria and Washington, rapidly industrializing, made the perfect market for cheap coal. The first railroad that made it across the mountains would earn its investors a pretty penny.

But the AL&H never made it to coal country—the company never found an affordable route over the Blue Ridge. It took the railroad 20 years to reach Round Hill, still just on the east side of the mountains. It made it no further. By the 1870s, West Virginian coal had found its way to eastern ports thanks to competitors who were successful in making their way over the Blue Ridge, and McKenzie’s railroad found itself floundering.

After twice changing ownership, by the early 20th century the railroad had found something of a footing. The railroad, finally christened the Washington and Old Dominion, carried light freight—mail, milk, that sort of thing—for customers in towns like Vienna and Herndon along the route. Without the golden goose that was West Virginia coal, times were lean. Seeking to cut costs associated with steam trains, the railroad electrified the line in 1917.(2) Instead of heavy trains stuffed to the gills with bituminous coal pulled to and fro by steam locomotives, the W&OD carried lightweight railcars with mostly domestic goods. Heavy industry it was not.

Without coal trains clogging up the line, the railroad was also able to tap demand for leisure travel. The company built a spur to Great Falls, the Potomac River waterfall which remains today a National Park Service park and popular tourist attraction, and began operating passenger service to the site.(3) Great Falls, along with resort towns in Loudoun County, turned the W&OD as an important part of upper-class leisure life of Northern Virginia and even Washington, DC; the Great Falls branch ran directly into Georgetown, to this day one of the most well-heeled neighborhoods of the nation’s capital.

Much the same way, it’s leisure that makes the W&OD such an important stitch in the fabric of Northern Virginia. Sure, some spandex-clad super-commuters bike the trail daily to work in Arlington and DC, but they’re the exception rather than the rule. That’s doubly true now; with coronavirus forcing the city’s white collar workers—the sorts of people with disposable income for a tricked-out road bike appropriate for long haul commuting—to work from home, the trail was dotted with families, old folks, and slow-going wannabe athletes like myself.

The trail traverses a diverse landscape, both natural and constructed. It passes a water treatment plant, a half-mile of auto body shops, and a college baseball field. The Four Mile Run ravine, the route’s most dramatic scenery, is bookended by two of Arlington’s most traffic-choked roads. There’s a playground, a dog park, a bird nesting ground. A sign warns that cyclists should yield to pedestrians, and both should yield to people on horseback. (I’m skeptical a horse has ever been on this part of the trail, but then again, why else would there be a sign?). But one constant is what’s above.

The power poles can’t be missed, big pylons carrying thousands of volts towering over you. Their regularity, every 500 feet or so, gives a bit of rhythm to the ride—30 seconds here, 25 there. Noticeable, yes, but when you’re on the move the pylons are just as much part of the landscape as the asphalt beneath and the trees to the side. The high voltage lines don’t quite stretch the entire length of the trail, but they come close. They’re always present, drawing little attention, just hanging over passers-by.

It might be a few miles before you start to hear the hum. It’s quiet, barely audible over the ambiance of walkers and cyclists. When you first notice it, it’ll sound like something natural, the springtime drone of insects lurking in the undergrowth. But no insect buzz is quite this regular. Once you notice it, the hum is ever-present. It follows you as you continue uphill, escapable only by leaving the trail entirely. Day and night, as long as the lights are on across Northern Virginia, the power lines above continue to drone on.

The power lines, like the rest of the trail, don’t necessarily feel like they have a particular history. They’re just there, no reason why or why not, natural as anything else. But just as the story of the W&OD can’t be told without the story of coal booms and busts, nor can it be told without looking at the power lines hanging above.

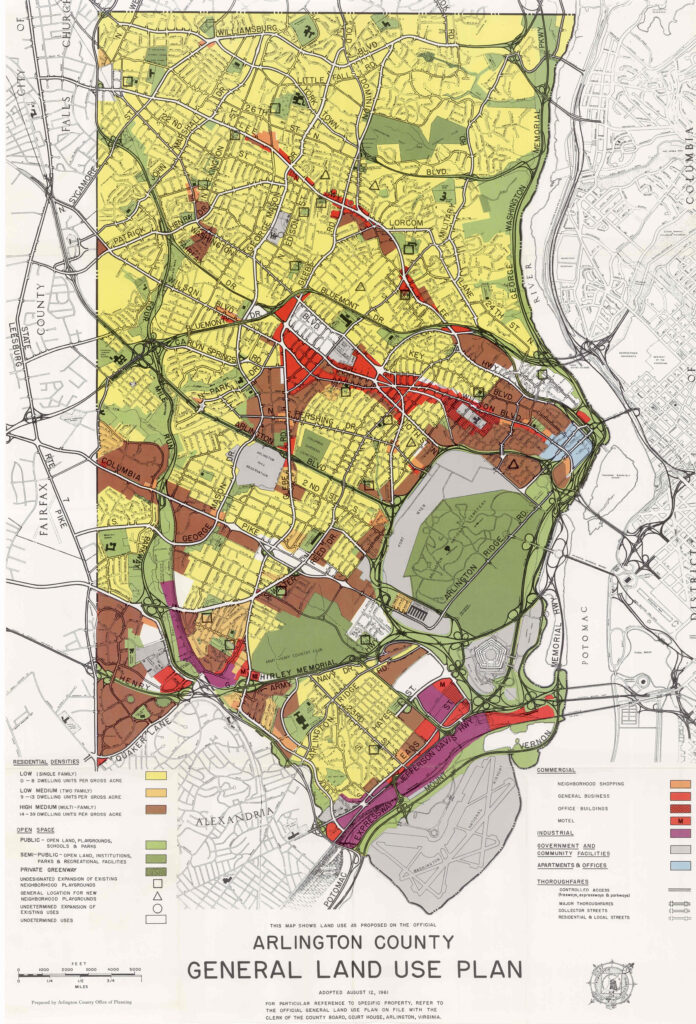

Without the power lines, the trail as it stands today almost certainly wouldn’t be there. The W&OD went under in the middle of the mid-century highway boom, and state planners saw the old rail right of way as a perfect conduit to carry thousands of vehicles. I first came across Arlington County’s planning maps from the 1960s while researching for a paper on DC’s freeway revolts, which successfully halted highway construction across the area. The picture is dire; shocks of green cutting through town, forests which still flanked the old rail lines, were to be replaced by divided highways.

That plan didn’t entirely come to fruition, though about 3 miles were used to build I-66, a major commuter highway through Arlington.(4) Scaling back the plans was one of the victories in a long struggle against urban highways which played out across the DC area and throughout the country. The state, which had acquired the land to build its highways, flirted with the idea of selling it off to private individuals but found a better deal with the power company. Instead of the right of way turning into a highway or more suburbs, power lines were strung up over the old rail line. Space below was freed for the trail.

The collapse of the moderately successful railroad which set the stage for the highway and power line plans was swift. By the middle of the century, railroads across the country were struggling. As freight shifted from rails to highways, railroads scrambled to keep solvent. The Washington and Old Dominion, a short line without heavy traffic or high-value goods, never stood a chance. In 1951, the railroad stopped running passenger service, its riders instead choosing commutes over brand new highways. That same year, it lost its mail contract as the postal service switched to trucking.(5)

In 1956, the W&OD’s owners sold the line to the Chesapeake and Ohio, a huge system which made most of its money hauling coal. The C&O hoped to use the W&OD to carry coal to a planned Northern Virginia power plant, but the plant never materialized.(6) In 1965, the C&O petitioned the Interstate Commerce Commission to allow it to abandon the line. By 1968, service ended entirely.

It’s perhaps fitting that the railroad’s birth and death were both marked by ephemeral dreams of coal. Coal was the 19th century gateway to modernity, birthing the industrial revolution in factories and mills across North America and Europe. The unbuilt coal power plant was meant to power thousands of homes as suburbs grew like kudzu across Northern Virginia. The Washington and Old Dominion had always sought to capitalize on the fuel for its investors’ enrichment. But it just never worked out.

There’s a thread here: the tracks were first laid in hopes of reaching coal country, bringing forward the industrial revolution. When that didn’t pan out, the railroad electrified its line to save costs. When it looked like the W&OD could be used to supply a coal plant powering suburban homes, investors gobbled it up. After that, too, fell through, the right of way was preserved first for cars, then for power lines. The story of the W&OD is a story of electricity, of progress, and of modernity.

What would the W&OD look like had its plans for coal hauling materialized? If McKenzie had ever made it to Hampshire County, the AL&H would’ve been among the first railroads to haul coal from West Virginia to an east coast port. Across coal country, from the southwestern tip of Virginia through West Virginia and into Pennsylvania, dozens of towns made their fortune on coal mining; dozens more made it on coal shipping. This was true even where railroads had to cut through narrow passes and winding valleys, with coal taking days to travel from mines to ports. Had McKenzie’s railroad crossed the Blue Ridge, it’s not hard to imagine a completely different pattern of development across Northern Virginia.

If the W&OD ever became the coal-hauling railroad its investors dreamed of, it’s hard to imagine we’d have the trail we had today. Whether bringing coal east from West Virginia to Alexandria or carrying it west to outlying power plants, the coal business might simply have been too lucrative to abandon. It’s not out of the question; nearly 70% of the country’s still-operating coal power plants receive shipments by rail.(7) Instead of miles of gently sloping trail carrying commuters and leisure cyclists alike, the right of way could still to this day be clogged up with half-mile-long trains overflowing with coal. Virginians should count themselves lucky to have escaped this fate.

There’s not a lot left, save the name, of the trail’s railroading past. The rails and ties are long gone. Trestles which carried trains over creeks and roads have been demolished and rebuilt. Certainly, there’s no record of the line’s role in the coal boom; what’s left only marks the short decades of passenger service. Some mile-markers remain, and while most stations have long since been demolished their locations are marked with informational plaques. The trail’s operators—the regional parks authority in tandem with a historical preservation group—have chosen these parts of the railroad to be worth remembering. Coal, it seems, is better off hidden.

My ride on the W&OD finished at Bluemont Junction. Back when the trains still ran, Bluemont Junction was where passenger trains turned off the main line to head to Rosslyn, Arlington’s quasi-downtown and the railroad’s quickest route to DC. The Bluemont branch was the first part of the line to be abandoned; it was the portion that partially became I-66, a few miles of highway with even fewer remnants of the railroad than the trail. But sitting at the junction, parked on a few dozen feet of orphaned, rusty track, sits an old caboose.

It feels anachronistic; a “caboose,” for me, is one of those words that evokes Thomas the Tank Engine, or old 19th-century steam trains. But the Bluemont Junction caboose is a vestige of the railroad’s 20th-century passenger service. This vehicle is one of several which ferried passengers from Alexandria and Rosslyn to Loudoun County and Great Falls.

As I walked around photographing the old train car, a family of four showed up. The kids put their scooters down and climbed up onto the caboose, peering inside. What decades ago had been a component of upper-class leisure travel, tied to a history of coal and electric power, is today a place of play.

That’s the sort of memory that exists of the Washington and Old Dominion Railroad. It’s become a place to get a breath of fresh air from the pace of daily life. It matters that the W&OD is what it is today. Without the trail, without the rail line before it, recreation in Northern Virginia would be all the poorer. But it also matters that the line’s coal history is hidden; decontextualizing a messy part of the railroad’s past means we lose an important part of regional history. Maybe telling the railway’s full history would turn off visitors; perhaps coal just isn’t sexy in a deep-blue area which cares about the environment. But uncovering the history of the trail would allow us to reckon with the forces that shaped development in the region.

Footnotes:

1. Harwood, Herbert H., Jr. (April 2000). Rails to the Blue Ridge: The Washington and Old Dominion Railroad, 1847 – 1968, p. 20

2. Harwood, p. 49

3. Harwood, p. 35

4. Harwood, p. 101

5. Harwood, p. 90

6. Harwood, p. 97

7. Energy Information Administration; see Table 6

Archives

Categories

Calendar

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |||