A Delicate System: Exploring Patterns in the Long Island Sound

By Elsa Dupuy d’Angeac

This project started with an investigation into how trash arrives on my beach and why it stays. To do so, I researched the presence of wildlife and the water quality at two beaches on opposite ends of Long Island Sound.

I grew up in New Rochelle, one of the most populated cities along the Sound. For the first 2 weeks of the Covid-19 quarantine, however, my brother Oscar and I stayed at our family friends’ empty house in Springs, East Hampton—a mostly summer community on the far northeastern tip of Long Island. A gray wooden deck leads from the house’s floor-to-ceiling windows to a low wall of sweetgrass, below which stretches white rocky sand all the way up to the Long Island Sound. The house’s deck trickles into a path of large smooth stones; these cut through the greenery in order for the deck to extend on stilts above the water. From there, a pulley dips and raises a staircase onto the slim stretch of shore. At high tide or when no one is using them, the stairs straighten, existing several feet above the water’s surface.

Colonies of seagulls live here in what seems to me constant motion. Their movements mesmerize me, allowing me to channel a pre-pandemic existence. I often observe their dance, commenting on their swirls like a critic at the New York City Ballet. During a storm at high tide one afternoon, I swayed along one edge of the ladder and peered through the slits between each step for shadows of the rocks submerged in the currents. I tried to repeat this during the following storm, but the wind trapped me at the junction between the edge of the deck and the top of the stairs. I squeezed all 10 toes into the ground and watched through whipping strands of hair as the wind moved across the water in indigo ripples. The seagulls surfed the wind’s waves with a grace and speed which put the city’s finest to shame. My torso wobbled, and at the wind’s forceful suggestion I headed back inside.

Springs is located in Northern Long Island, right as it juts into a disjointed strip. The house itself sits on Gardiner’s Bay, where the Long Island Sound approaches its widest area. Even during a storm, Gardiner’s Island decorates the horizon, making the expanse feel smaller than it is. If the sky was clear we kept the back doors open, allowing a crisp saltiness to filter through the kitchen, a reminder that healthy water was lolling mere feet away. In my opinion, Springs might be the perfect spot to live in Long Island, as it is home to the highest amount and variety of birds in the surrounding area. I recently learned that the abundance and variety of birds in front of the house is largely due to laws which prevent hunting waterfowl circulating and inhabiting Gardiner’s Island. In fact, on December 15, 2018, Larry Penny, a writer for The East Hampton Star, recorded 4,225 scoters, more than half of which were spotted in the area surrounding Gardiner’s Island. Furthermore, the healthy water supports the development of marine wildlife, which contributes to a balanced ecosystem.

The Long Island Sound measures 1320 square miles with 600 miles of coastline and an average depth of 63 feet. Almost 9 million people live along the Sound’s coasts today, compared to a mere 117,000 in the 1950s, before post-war housing projects created a population boom. In 1972, Congress passed the Clean Water Act, which promised to prevent oxygen levels in the water from lowering by regulating waste discharges, oil spills, and other pollutants. And so began a decades-long effort to clean up the sound.

The Long Island Sound Study (LISS) was created in 1985 in order to monitor the water’s health. LISS in turn established the Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan in 1992, initiating environmental protection projects. New York and Connecticut created the Habitat Restorative Initiative in 1998, aiming to restore rivers and enact water quality standards. This plan included a Total Maximum Daily Load, which would reduce nitrogen pollution by 58.5% through modernized wastewater treatment plants. Today, nitrogen dumped into the water has decreased by over 50 million pounds since the early 90s. HRI continues to restore thousands of acres of natural habitats and hundreds of miles of rivers through projects which engage the communities surrounding highly polluted waters.

Oscar and I are now in our childhood home in New Rochelle. From our terrace, I watch the Long Island Sound change color in the spaces between our neighbors’ houses. All afternoon, the wind splattered hail across the window, blowing our front door open and sending my dogs into a barking match. Buds which often seem light green and burgundy appeared bright yellow and red against the black blur of sky and water. Now, the hail has stopped, but the dogs are still wary of the sound of the wind emanating from the chimney. The buds on the trees have darkened and a fat rainbow is bending from the pale purple sky into the gradient water. Cobalt to grey to white.

When the sky is clear, Emily, my best friend from home, and I cope with social distancing by sitting 10 ft apart from each other on the neighborhood beach. Decked in masks and gloves, we climb the gate because I can never remember the code and tiptoe down a narrow, steep gravel path, hoping the neighbor’s ferocious husky won’t be lurking behind their fence. Rarely do we encounter anyone, yet we’ve developed a fool proof plan for maneuvering such unwanted circumstances. A square stone landing exists as the neighborhood’s haven against the sand. From there, masters at navigating the trails of trash and algae in the sand, we trace the tall stone wall which protects properties against the water’s urges. Through a hidden staircase, Emily and I climb onto a section of the wall bordering a yellow dilapidated house that I know is haunted. Behind us, rusty lawn furniture and broken kids’ toys litter the brown backyard. Crumbling windows creak against the breeze and I swear someone just peeked out the floral curtains at the top left window.

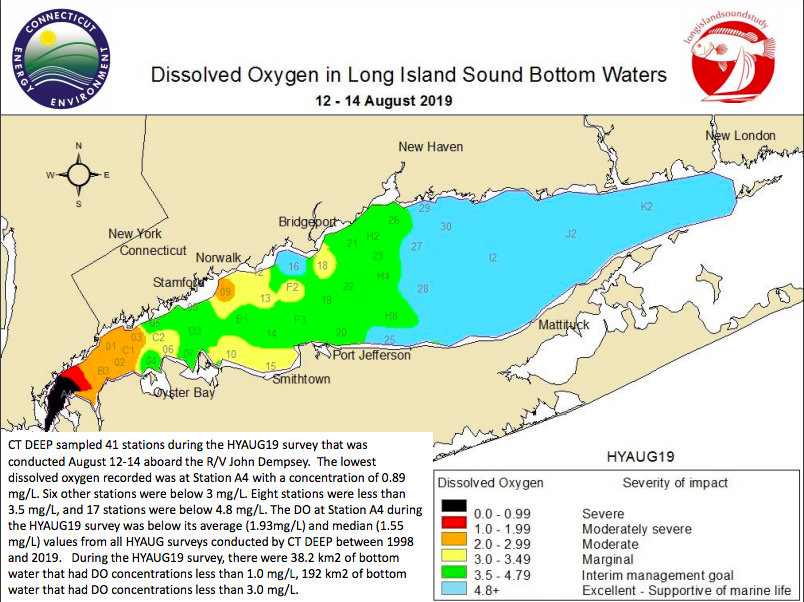

The wall is always decorated with seagull and geese droppings, but I’ve never spotted as many birds as I had in Springs. Not colonies of swooping and dancing ones anyways. Coastal birds such as seagulls and black scoters feed mostly on bluefish and striped bass. As these are mobile species, they are not severely affected by a process called hypoxia. However, the fish that these fish feed on may be. Hypoxia occurs when nitrogen pollution causes excess growth of phytoplankton, zooplankton, and algae (see this graphic for a visual). The eutrophication of water occurs as algae and other plants feed off of nitrogen, causing algae blooms to cover the water’s surface. The decomposition of these blooms lowers the dissolved oxygen levels of deeper water, which can create suffocating conditions for marine wildlife and their habitats.

The water quality near the house in Springs supports a healthy variety of marine life, allowing for an abundance of coastal birds. In New Rochelle, high levels of hypoxia severely impact the development of stationary fish, distributing harm throughout the entire surrounding ecosystem. At home, seagulls exist in much fewer numbers and black scoters are rare. If these do appear, they’re usually feeding on discarded remnants spat from the Sound’s bowels rather than on any friendly fish.

Rows of trash masquerading as algae extend toward the Sound’s foamy surface. My friend jumps off the wall and lifts something from one of the mounds. Her thumb and forefinger a delicate crane sifting for treasure. She squints at the object of former desire and grunts her disappointment. Just burnt plastic. She laughs, “It kinda looks like a little j, filter and everything.”

Her hunt is an attempt at playing our favorite game from when we were little, a ritual which my mom found upsetting and gross. My brother Marcel would set the timer: 4 minutes! Ample time to crawl through the mounds for hidden gems. Little trenches of plastic chairs, plastic limbs, plastic bucket debris, red plastic solo cups, plastic hangers, plastic cutlery, poisoned carcasses. At the alarm, we would race back to my brother, who would declare the winner. He’d ask us where we thought the pieces came from and we’d invent elaborate origin stories, whispered as if our treasures were outlaws. The prongs and neck of a fork from a street fair off the coast of Italy, discarded after shoveling clam linguini onto drooling tongues. The wind had swept it into the ocean’s unsuspecting currents. Slightly injured from battling electric eels and piranhas, rejected from the intestines of Nemos and baby turtles, it had finally landed in a space where it felt welcome. We’d trade and sort our items into separate piles until we could carry them home and put them in glass jars to join loot from previous adventures. Sometimes we’d forget them on the stone landing and my brother would comfort us by assuring us that was ok because now all their friends wouldn’t miss them. When my mom found out about our customs, she decided to teach us less-than fantastical origin stories, showing us to play beach-cleanup instead. Imitating pirates was much more fun though so we kept doing it when she wasn’t watching.

Today, the piles of trash make me wonder why our beach has so much more pollution than other ones I’ve visited on the Sound. I learned that the water’s hydrology, or circulation patterns, explains this phenomenon. Water flows into the Long Island Sound from the Atlantic Ocean from both the East and the West. Both fresh and salt waters meet in the Sound, affecting the water’s salinity. Mixed bodies of water such as the Sound are called estuaries. At the Eastern end, water flows directly from the Atlantic Ocean through a channel known as The Race. On the West, ocean water flows through the Hudson River and the East River before reaching the Sound by passage known as The Narrows. As a result, currents are much stronger in the East, near Springs, than in the West, near New Rochelle. In “The Race” and the Sound’s wider areas, the tide follows a regular estuarine circulation from East to West. In “The Narrows,” however, this strong westward current pushes along the seafloor past Westchester’s coast. At the same time, surface tides from the East River flow eastward along Long Island’s coast. According to Mario E.C. Vereira’s “Long Term Residual Circulation in Long Island Sound,” this creates a counterclockwise gyre in The Narrows, which traps pollutants on shores such as mine in the Western Basin.

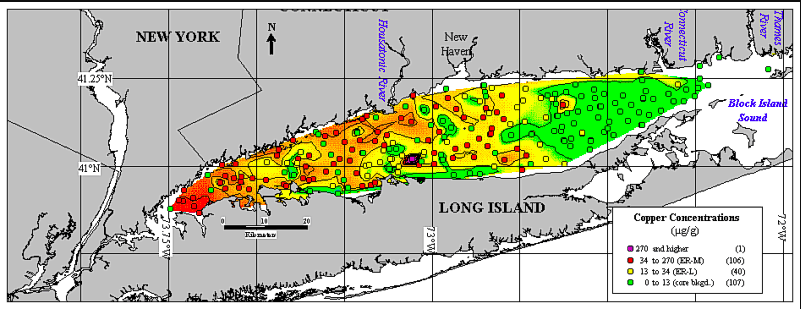

This map shows the distribution of copper throughout the Sound, highlighting the water’s hydrology. It also mirrors the trajectory of pollutants throughout the water, thereby creating a visualization of their voyages and inevitable arrivals at beaches like Echo Bay. Although the map does not include the water in front of Springs, it is clear that trash would accumulate at a higher rate near my home than near Springs.

Em flicks her plastified wishful thinking into the trenches, reuniting it with its friends in a nest of neon candy wrappers and a spiraling thread that glimmers purple. It reads: “DORITOS: Spicy Sweet Chili.” Accustomed to these unusual habitats, she regains the secret stairs, dry algae crunching under her new Vans. She hoists herself back onto the wall, sinking into its comfortable crevices. Pink ripples decorate the water; a lavender haze blurs the horizon line, yet to the left, gravel and treetops still appear orange.

“Dude I wish it was hot enough to go swimming,” Em comments. I remind her that when we were little we thought the water was too gross for swimming. Bands of algae usually covered the water’s entrance and foam bubbles populated the shore like beige fish eggs.

Algae blooms form and decompose in the summer, which is when hypoxia levels are highest. High temperatures worsen hypoxia by increasing the temperature difference between the surface waters and the bottoms waters. This increased division prevents water from flowing between the layers, hindering the transfer of oxygen between water layers. Hypoxia affects the development of fish species and their habitats in a variety of ways and can possibly result in population declines. The reduced number of fish might impact the animals who feed on them, such as seagulls and black scoters. An interview through LISS with Dr. Krumholz explained the complexity of the effects of hypoxia on marine wildlife. Certain fish can swim away from areas severely affected by hypoxia. Some stationary species, however, are unable to leave their habitat for safer waters. For instance, bluefish and striped bass survive hypoxia at higher rates than flounder. Furthermore, fish benefit from increased levels of nutrients such as phytoplankton because there is more food.

One brief summer, a wooden dock inhabited the waters some 30 feet, a mysterious haven where we could soak the sun and whatever else. We were too tempted by its inexplicable presence and distance from other beach dwellers, mostly just my family, not to explore the matter further. One afternoon, we waded through the crowd of slimy algae, jagged rocks massaging the balls of our feet. The cold water initially warranted shrieks, but felt fresh once we reached darker depths. Our shrieks remained, however, as we taunted each other about the creatures lurking just beneath our toes. A rickety metal ladder clung to the edge of the dock, the surface of which was lightly splattered white and black. Seagulls had visited this space before us; we didn’t mind sharing and we hoped they wouldn’t either. Satisfied with our investigation, we returned to our makeshift island by canoe throughout the remainder of the summer, picnic and various necessities in tow. If we weren’t napping or eating, we observed the few seagulls who had claimed nearby rocks, just like the striped bass occasionally inspecting our toenails.

Certain organizations exist solely to monitor the activities of the Sound and its numerous occupants. The Long Island Sound Water Quality and Hypoxia Monitoring Program conducts routine water quality surveys throughout the year by collecting nutrients, phytoplankton, and zooplankton from various stations. Scientists test hypoxia levels in the water from June to September by sampling over 50 stations throughout the Sound for dissolved oxygen. Scientists measure how many days the water is in a hypoxic state for as well as how wide the hypoxic areas are. Scientists conduct studies using a device called a Conductivity Temperature Depth Recorder, which uses a Rosetta Sampler to collect water from different layers. The combined data helps scientists understand the severity of hypoxia effects on the water.

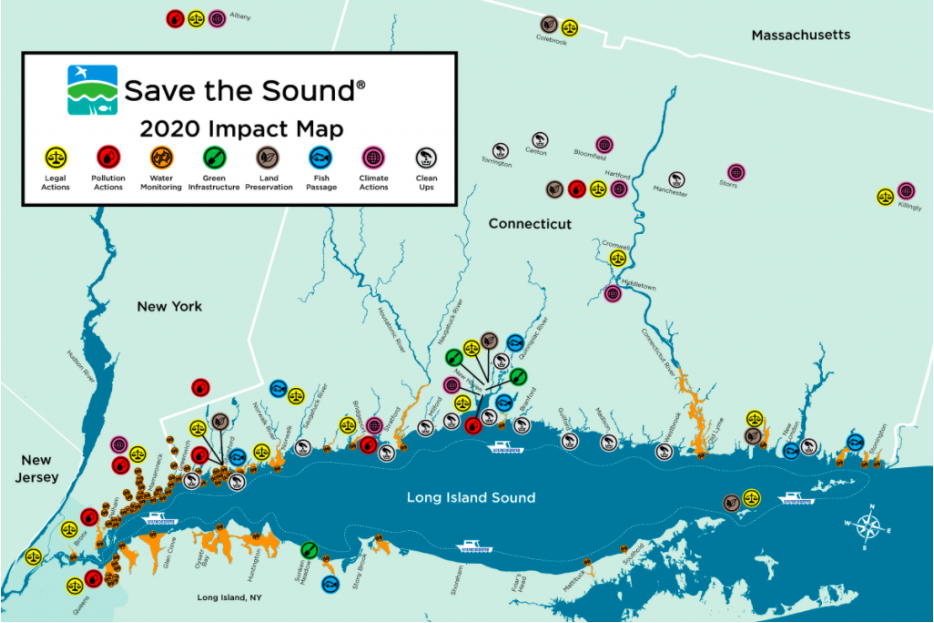

Save the Sound’s interactive map Sound Health Explorer allows users to explore changes to the Sound from 2004 to the present.

All three maps reveal the successful outcomes of projects to mitigate hypoxia and its consequences. Plans to counteract hypoxia involve lowering the Sound’s nitrogen intake, which in turn may lower nutrient levels. It is difficult for scientists to weigh the consequences of reducing food resources with the benefits of decreasing rates of hypoxia. Separating the specific outcomes of each of these systems from other elements such as climate change or fisheries is also a convoluted process. In order to cope with the complexity of hypoxia and its effects, scientists have developed computer models which mimic the Long Island Sound, including patterns of water circulation, production of algae blooms from nitrogen, and their effects on oxygen levels. These allow scientists to investigate different environmental protection plans and foresee their effects before testing them on actual habitats.

Wastewater treatment plants dotting the Sound’s coasts are responsible for a large percentage of the water’s nitrogen pollution. These plants release processed wastewater into the Sound which often contains high levels of nitrogen. Thanks to stricter regulations, the water’s nitrogen levels have decreased significantly from 33,000 lbs per day from New York of 1998 to 13,000 lbs per day in 2019. Despite significant system improvements as well as discharge quality standards, nitrogen levels remain high, contaminating the water and contributing to hypoxia. Due to the proximity of towns near the Eastern end of the Sound to the ocean, nitrogen released from plants in this area will infect the water at a lower rate than the one in New Rochelle. In addition, weather conditions can also pollute the water by affecting a plant’s ability to treat waste. I recently learned that rain and storms can cause plant pipes to overflow or burst, liberating waste from its treatment and contaminating the Sound more intensely than nitrogen.

In the summer, my best friend and I often criss cross the Sound on her family’s boat. We usually wile away a couple hours picnicking and maybe belly flopping front flips into the water. On one particular post-storm venture, however, clusters of poo bobbed merrily about the water’s surface like baby otters. Unable to find refuge from the pungent creatures, we abandoned our picnic for a lunch far from the shore. I live 6 minutes away from New Rochelle’s wastewater treatment plant, where badly maintained pipes were damaged by the storm.

In 2015, Save the Sound sued Westchester County for violating the Clean Water Act by repeatedly releasing untreated sewage water into the Sound. In 2017, Governor Cuomo allocated $69 million to fixing sewage systems throughout New York state, including $17.6 million specifically targeting New Rochelle. Soon after, New Rochelle completely renovated the city’s sewage system and water treatment plant.

Save the Sound is the most active organization protecting Long Island Sound’s water and wildlife, the surrounding coastal habitats, and the air inhabitants breathe. Save the Sound restores natural resources, organizes activists, and works toward bringing environmental protection to the forefront of governmental policies. Save the Sound’s boat “The Soundkeeper” patrols the waters looking out for pollution and tracking water quality. In fact, “The Soundkeeper” was an essential element of the legal suits against Westchester County. Save the Sound coordinates Connecticut’s involvement in the International Coastal Cleanup, rallying 15,500 volunteers who rid Connecticut of around 110,000 lbs. of trash each fall. A couple years ago, our neighborhood started funding bi-weekly beach clean-ups.

When I was little, I didn’t question the trash’s presence on our beach. As far as I was concerned, it had trekked across oceans and far away lands simply for our amusement. I eventually grew to care for the natural habitat as much as I once had for its plastic tourists. Yet, the process was slow. I nagged my parents about the state of our beach more often than I partook in clean-ups not mandated by my neighborhood. Today, during the Covid-19 pandemic, the game we played just reminds me that we can’t touch anything with our bare hands, especially not washed up trash, and we definitely can’t be close enough to whisper secret theories. Even worse, it makes me miss my brother, Marcel, who I haven’t seen in months and don’t know the next time I will. In a reality not constricted by quarantine, however, my family and I approach the beach as a beloved wet dog in need of a spa treatment. Combing through the mounds by the back wall, we fill our backpacks with their contents. Uninvited plastic guests are destined for the trash, but my dad collects the algae for compost.

Since the pandemic, hardly any trash has visited our beach. Yesterday, I found some chatty seagulls and the end of a rainbow.

Archives

Categories

Calendar

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |||