Carrying a Backpack Full of Stones: A meditation on the past and present of the post industrial landscape

By Celia Hurvitt

Granite quarries dot the pine forests of coastal Maine. Once the primary source of economy in this small state, they are now abandoned, tucked behind tree lines and out of sight. Through a series of reflections on time, memory, and property, this essay aims to answer what should be done with these post-industrial sites? And, how can we reconcile with the violence inflicted upon them in the past?

There is a very specific way that Maine granite looks when it has baked in the sun for a long time. The faces of rock start out dark grey, rugged and sharp but when left in the sun for long enough their edges soften and they turn from grey, to white, to pink. You can see them on spectacular display at the beach down the road from my house. Where there’s no sand but rather graceful mountains growing out of low tide mud, turning rosy and shimmery in the early evening light. My dad was the first person to teach me the word mica. He picked up a piece of stone one day on a hike and pointed out how the silvery scales in the granite made it look straight out of a jewel box. He told me that the micah made the granite very valuable, and because of this it was used to build everything from kitchen countertops to big buildings in New York City. Mi cah, I loved the word, the way it sounded both precious and ancient. After that I kept my eyes peeled for mica on every hike, soon realizing that it was absolutely everywhere. I later learned that Deer Isle is home to a very unique and desirable pink granite. Because of this, almost every rock I came upon had a rosy, sparkly sheen. I drove my dad crazy by making him tote all the rocks I found home in his backpack.

I am reminded of these hikes as I go down to the beach to pick out rocks that I’ll use to weigh down a kimchi fermentation project I have started in my kitchen. I need the perfect size, ones that are small enough to slip inside the diameter of wide mouth ball jars, but not too small as to sink into the sea of kimchi. I find quite a few, and being unable to resist their familiar twinkle, I end up with far too many stuffed into my backpack, just like I had as a child. Heavy backpack in tow, I head back to the road. I look up ahead and see the sign for the quarry road. I hadn’t planned on going there, but now I was sure I wanted more rocks, driven in part by the desire to find the most beautiful, the perfect size. Where better to find some? I think to myself as my back groans a little under the weight of the rocks already in my bag. I’ll just go have a look.

The quarries are up a windy dirt road from the beach that leads you away from the shore and into the forest. The path takes you into a different world—the trees here are all evergreen and covered in fluorescent moss, brilliantly contrasting from the dull, brown hues of early spring at the beach. There are four quarries up this road, two of them are inaccessible because of the houses built directly overlooking them, but one, Collin’s Quarry, is tucked away in the woods behind one of the houses, making it easy to slip into unseen. I ignore the “posted private property” signs, and quietly make my way past a stand of white pines, pushing bows aside to peek through at the glassy, mellow water. The quarry truly looks like an oasis. The picture of serenity is entirely hidden from the outside by trees, so it just looks like a continuation of forest until you see the granite creeping out onto the forest floor. I squeeze myself through a cluster of trees, ditch my backpack, and scamper up a large slab of granite that protrudes over the silent pool, making it the perfect seat.

I inhale the smell of sun and pine trees and of something else. Gin? I smile when I see a juniper bush valiantly crawling its way through the cracks of granite to my right. I am far enough from the road that I can’t hear the cars. The dappled sun through the trees brings heat to my face. A kingfisher dives into the water.

A landscape that appears wild and serene, on closer inspection tells a complex story. The pines around me are white pines, typical first succession forest plants that grow back easily after some large disturbance event.(1) Like the juniper bush, most are very small and scraggly, struggling to grow out of rock. Unlike the smooth domes that I take naps on at the beach, the rock that I swing my legs against is scratchy and broken in irregular places indicating that it had been cut and blown apart once. When I look closer, around my seat there are many pieces of rusted metal, leftover from clamps, hooks and chains used to lift giant stones out of the deep pool. I am sitting in the post industrial landscape of a working quarry.

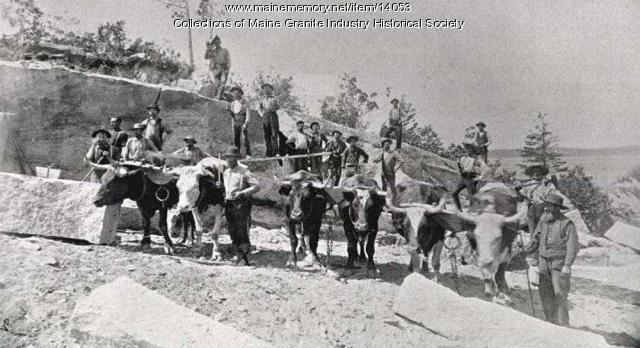

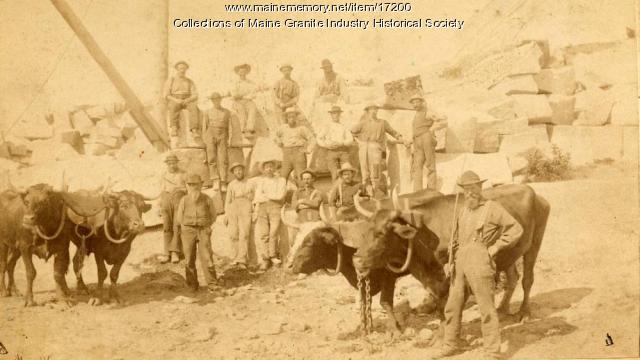

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the quarrying industry provided jobs for thousands of laborers, mostly immigrants, supplying building material and pavement for a young nation. But when construction techniques and road materials changed, the industry declined, and most of the early stone companies stopped their operations. Collin’s quarry was in use primarily in the early 1900s and it provided the granite for various important buildings in New York City and Boston.(2) This site is one of the many scars of the industrial revolution that has made its mark on the landscape of the northeastern United States. Along with Massachusetts and Vermont, the state of Maine produced the majority of the granite that built the major cities of the northeast and granite remained its primary source of economy through the first part of the 20th century. Hancock county, where I live, was among the top two granite producing counties in the state.(3) Now it is common to find quarries spotted amongst the woods of coastal towns, creating oases in the middle of scraggly forests, and providing prime real estate for a growing number of vacation homes.

Sitting at the edge of this quarry, I reflect on how the human alterations to landscape were profoundly obscured but by no means entirely erased. The remnants of the industrial age poke out everywhere, demanding to be seen. How do landscapes remember what human beings cannot? Will the quarries of New England ever completely transform into forest again or will they always be marked by their industrial past? In a capitalist structure, land is a commodity, measured by quantity and production value. Landscape, on the other hand, holds more meaning, Anthropologist Tim Ingold, describes landscape as “qualitative and heterogenous.”(4) In other words, though the home owners at the end of this road could own many acres, they chose the beautiful landscape of the quarries to build their homes near. There is inherent value in these post industrial landscapes even though their industry is long gone. The value of the land is no longer for production but rather for the consumption of its “wildness.” What do post industrial landscapes do when their industry dies? Especially as “nature’s” gradual return to these areas is also commodified, and access to natural spaces becomes available to only those who have purchased this “private property.”

In many places, quarrying was such a huge industry that it transformed regions and their towns, leaving scars on landscapes that are far more apparent than the ones at Collin’s. Italy’s Apuan alps lie north of Tuscany and are home to the greatest amount of marble in Europe. The hundreds of quarries smattered throughout the mountain range have been used since Ancient Rome, to harvest this precious white gold. Sculptors such as Michelangelo and Berini have carved the most foundational pieces of Renaissance art from such marble. The stone therefore, became a glorified symbol of Western civilization. It was emblematic of the lengths that human civilization would go to conquer the natural world, showcasing a very physical ability to find, extract, and ultimately sculpt this precious material. But behind the scenes of this symbolic stone, the mining industry that sprung up around these quarries was tragic and severe. Men lost fingers, limbs and were crushed by moving huge blocks of marble. Bodies were blown up with dynamite, and people in nearby towns suffered lung problems from breathing in rock dust all day long.(5) These factors are common throughout quarries around the world. It is a harsh industry that causes many deaths and leaves behind even harsher landscapes. When abandoned, stone quarries are often so devoid of soil that it is almost impossible for plant life to grow back. Many of the holes are filled in with water, providing a habitat for frogs and birds, or swimming holes for the public to enjoy. In many cases the pools of water become polluted from the rusted equipment that is often left in the bottom. Many are simply deemed too toxic and turned into landfills.(6)

The quarries that are restored and opened to the public are often beloved spots, the post industrial site providing a stunning landscape for people to enjoy. Quarries have been turned into public swimming holes, parks, and even performance spaces and ampitheatres. In many areas quarries and other post industrial sites such as mines and railroads have been converted into tourist locations, with didactic signs posted around explaining their histories. In Shanghai China, a former abandoned quarry yard has been converted to a botanical garden and park. Quarry garden has become a landmark in Shanghai. It charges money for tours, but is otherwise free, drawing in city dwellers and foreign tourists. The idea behind the quarry is to show how beauty can rise out of rubble.(7) It aims to create a beautiful oasis of nature within a city while simultaneously showing the exploitative past of quarrying in China. In Portland Connecticut, across the river from Middletown, a former quarry has been turned into an amusement and waterpark, with slides, games and food. Here it is a more blatant tourist attraction, charging admission and profiting off this post industrial site. As exemplified with these two cases, a lot of the interest in converting and utilizing quarries has to do with their beautiful aesthetic qualities, but also it seems to stem from a desire to rehabilitate them due to their violent and exploitative pasts.

While the granite industry was in many ways harsh, there are still those who harbor nostalgia for it. On the tip of Deer Isle, lies the town of Stonington. As its name suggests, it was one of the many towns along the Maine coast that was founded and populated by the granite industry. Along with being the largest lobster port in Maine, Stonington is home to Crotch Island, a mound of granite about a mile from the waterfront downtown. The granite harvested from Crotch was foundational for many of the large buildings during the 20th century, notably the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, pillars for the Brooklyn and Williamsburg bridges and the JFK memorial in Washington, DC.

I stand out on the pier in Stonington looking over the water to Crotch Island. Behind me there is a street that is lined with gift shops and lobster shacks that must look very different from the boomtown days of the early 1900s, when an estimated 10,000 Europeans, mostly Italians, came to Stonington to work in the quarries. Back then, there were boarding houses, stores and special schools set up for these workers, all bringing new life to the previously isolated coastal town.(8) An article in the Los Angeles Times, written in 1992, details the experience of one young man, Oliver, working on the Crotch Island quarry and feeling nostalgia for an industry that has fallen.(9) Oliver went out to the island every day with his three co-workers because although concrete had been traded for granite across the construction industry, there was still a sliver of demand for the special pink granite on Crotch. This quarry has since closed. While at Collin’s the vestiges of the past only surface after a second look, the quarry on Crotch shows its history clearly branded into the landscape. The 450 acre island is littered with rusted machinery and haphazard mountains of unusable cut granite. I imagine the landscape is slowly going to resemble Collin’s, but there are people here who are intent on remembering what the landscape will never forget, the industry of its past.

November through May is known fondly as “trespassing season” on the coast of Maine. Small coastal communities such as Deer Isle and Blue Hill, the town I live in, essentially follow an annual boom bust cycle. During the summer months, my 2,500 person town doubles as homeowners, primarily from major northeastern cities, move up north to avoid the heat. The invasion isn’t all bad, some, like my parents, welcome them with open arms happy that their business will survive one more winter. But we all can’t help but breathe a collective sigh of relief when September comes, and suddenly life is back to normal. It’s in these moments that I go trespassing.

In the winter our favorite family walk is down to an enormous estate that looks out over the bay. There is a pond on the property, when it freezes over, we often skate there because of its stunning view over the water. In retrospect this seems like some sort of profound political statement, us throwing to the wayside rules of private land and doing what we wished, but in reality it wasn’t intentional nor out of the ordinary. Most of my friends’ families did things like this too, it seemed only natural to use the land around us when it was uninhabited for nine months a year. Therefore I never worried about encountering anyone on my regular off-season runs to the Collins quarry.

A few days after my foray for kimchi stones, I return to the quarry. I have started running again in an attempt to get outside during the Covid-19 quarantine. It’s April now, Spring is starting to rear its head, and forgetting the unusual circumstances we are in, I don’t expect to see anyone on the quarry road. After running up and having a short rest, I start home. A large poodle dashes up to me and hits me with a force that stops me in my tracks. I laugh as it jumps all over me, and then catch sight of its owner rounding the corner of the road. When the dog doesn’t relent its affectionate smother, and I begin to feel confused. Why isn’t she calling her dog? The woman is standing still, watching all of this unfold. Not knowing what to do I put on my headphones and try to outrun the dog, but just as I am passing her I heard her speak.

“How are you?”

“Oh,” I responded, “I’m doing well. How are you?”

“No” she shook her head, “who are you?”

I was taken aback. Who in the world are you? I thought. I replied warily with my name, not yet indignant but soon to be.

She replied “Well are you from here or just visiting?”

This made me furiously angry, all I wanted to do was to prove: yes, I was from here! I wanted to shake her, to thrust my birth certificate in her face and show her that I was born right here, in the village of 100 people outside of the town of 2,500 and that I belonged. But I didn’t do that (for a host of reasons one being that it employed a sort of nativism that I am very opposed to) and I merely said,

“I live here,” in a cool voice and continued running.

I later learn that this individual is one of the owners of the quarry front property up the road, she is a seasonal resident, one of the many that has fled their city homes due to Covid-19. What happened between us could just be brushed off as a nasty encounter, on a bad day, between two neighbors who are both facing the crushing existential reality of a global pandemic. But I also think it makes sense to think of it through the context of land and landscape. She became protective of the land that she felt ownership over because she bought it. She thought of the quarry as land, a commodity, rather than as a landscape, a living entity with memory and meaning. It didn’t matter that she only understood a small fraction of its history, because its function to her was as an object rather than a subject. I think if you look closer, the potential consequences of this encounter can be devastating.

It seems that the quarries being private inflicts a new kind of violence on land and community. Especially exacerbated by the pandemic, private spaces like these disconnect communities from the natural world. As exemplified through the marble quarries in Italy, the brutal past of the industry has already wreaked havoc on the land, making it inaccessible for a long time. Now that these sites are post industrial, it’s important to reopen them to the public. Profiting off them, like in the case of the quarry in Portland Connecticut, doesn’t seem to be the answer. This presents the same problems that always arise from using a landscape for capital gain, pollution erosion and carelessness. Making the quarries accessible in a non-profit driven way on the other hand, could be wonderful. The Blue Hill Heritage Trust is a land trust in my town that has been working for the last 30 years to preserve land for recreation, habitat, and organic farming.(10) The land trust is above all community minded, interested in improving the quality of human life and the environment into the future. Spending time at Collins Quarry makes me wonder, could making this area quarry into public property offer some sort of reconciliation, from the initial violence of extraction to the devastating effects of a small town losing its industry? I don’t know if this would help, but closing it off to the public, making its power, legacy, and history a secret certainly doesn’t help.

We have to believe in the forgiveness of landscapes. After the destruction is over, the cranes roll away and ghosts flood into cavernous hollow lands, we mustn’t forget what happened. We must play among the ruins of the post industrial landscape, be a part of the healing, and do the work of imagining a different way of coexisting with the land.

References:

(1) Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. The Mushroom at the End of the World: on the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton University Press, 2017.

(2) “Maine Memory Network, Maine’s Online History Museum, a Project of the Maine Historical Society.” Maine Memory Network, www.mainememory.net/.

(3) Berleant, Anne. “The History of Maine Granite Runs Deep.” The Castine Patriot, 31 July 2014.

(4) Tim Ingold (1993) The temporality of the landscape, World Archaeology, 25:2, 152-174, DOI: 10.1080/00438243.1993.9980235

(5) Locatelli, Luca, and Sam Anderson. “The Majestic Marble Quarries of Northern Italy.” New York Times, 26 July 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/26/magazine/the-majestic-marble-quarries-of-northern-italy.html

(6) National Geographic Society. “Quarry.” National Geographic Society, 9 Oct. 2012, www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/quarry/

(7) ASLA 2012 Professional Awards | Quarry Garden in Shanghai Botanical Garden

(8) “Maine Memory Network, Maine’s Online History Museum, a Project of the Maine Historical Society.” Maine Memory Network, www.mainememory.net/

(9) Hidlay, William C. “Last of Old Maine Granite Quarries Keeps Alive Solid Tradition: Crafts: Four Men Are All That’s Left of an Island Industry That Once Employed Thousands. But the Business May Be in the Midst of a Renaissance.” Los Angeles Times, 5 Jan. 1992. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1992-01-05-mn-2357-story.html

(10) “Blue Hill Heritage Trust, a Community-Based Land Conservation Group.” Blue Hill Heritage Trust, bluehillheritagetrust.org

Inspiration:

Thank you to my mother Mary Alice Hurvitt, and neighbor John Mcmillian for your insight and ideas.

Archives

Categories

Calendar

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |||