Refusing to Produce During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Anthropocene . Capitalism . COVID19 . Op-EdsAn interesting graphical depiction for the word change is that, when it occurs in our lives, change forces us to leave our state of inertia in the past, altering the general direction of our future. But extreme changes, such as those caused by COVID-19, are different. This epidemic, like other uncontrollable disasters, forces humans to move in uncertain and often unwanted directions. Suddenly, we have to face anxiety, uncertainty, confinement, sickness and death, sometimes all at the same time. Rather than feeling like a change of direction, these changes can feel like falling downwards.

This uninvited change has dropped the structures we so often take for granted, such as our social life, our work routines, our patterns of consumption, etc. Imagine these structures as what constitutes our floor, that holds us in place; imagine, now, that our floor has suddenly crumbled. This is our fall. But amidst the angst and suffering that comes with the drop, we might find hope: all of the fragments of our past structures are falling with us, giving us the rare chance of picking the parts that we care for, to start reconstructing our foundations and formulating new futures.

This “crumbling floor” metaphor can clarify the importance of picking the right pieces of what will constitute our future after COVID-19: this is not the time to piece productivity and consumption back together. Those with financial power are obviously interested in advocating for alternative ways to keep the productive system (that maintains them in power) alive. Adopting the capitalistic discourse, we think that producing and consuming is the way to resolve the grief we feel for the future we have lost. Instead, we should focus on how the future can be made differently.

Historically, productivity has been established as the hegemonic guide to people’s routines. Through the compelling discourse of progress (commonly seen as both a cause and an effect of the industrial revolution) we have trained ourselves and others for a life centered in work — what the Anthropologist E. P. Thompson has called work-discipline (1967). Most of our social structures focus precisely in maintaining our work-discipline — from schools to the boss-worker relationship, we are constantly learning and teaching the importance of work in human life.

However, in maintaining our work-discipline we are also maintaining monetary and social inequality. To maintain our pay, we are forced to produce from home; then, we are asked to show, prove, digitalize, photograph, or record our work. Despite the epidemic, surveillance is still necessary, to guarantee that we are working as expected — and, quite often, we do this surveillance ourselves. It matters not that we are at home: if the work can reach us, so can our hands reach the work.

When we choose to actively refuse to revive and maintain our productive systems, we get insights that were impossible otherwise, that show how our system functions through inequality. Take, for example, how non-medical essential workers are now being pictured as heroes of the crisis. It is certainly the case that these workers should have more prestige in our productive system, but why do we only name them heroes under the current circumstances? Because they are the bearers of the productive system, and not because we suddenly value their lives. This perspective clarifies how, in reality, these workers are hostages, people who also want to go home but cannot. They work because not working is suicide — with no pay and no healthcare otherwise, they are left with no choice. We should not focus on just praising their unhuman efforts; rather, we should deny the underlying unhuman system of production and consumption. If they are heroes, let their pay be equally prestigious.

A federal manifestation of the necessity to refuse productivity occurred in Brazil last week. The Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro made an unfortunate appearance on national television, asking all Brazilians to stop social distancing and return immediately to their productive lives. Going against all scientific and medical evidence, Bolsonaro defined COVID-19 as a “measly cold” and said that the country would fall if people stopped working. The backlash was intense, with politicians and activists taking local control and refusing to follow the president’s ludicrous speech. For some people in power, seeing their productive apparatuses halt hurts more than seeing their people die.

The urge to overvalue work in our current context is an especially hideous instance of alienation because it strikes us when we are the most vulnerable, and it is the antithesis of what we need in such times; we must fight crises with affect, care and solidarity. At this time of exception, to refuse to work is to claim our humanity.

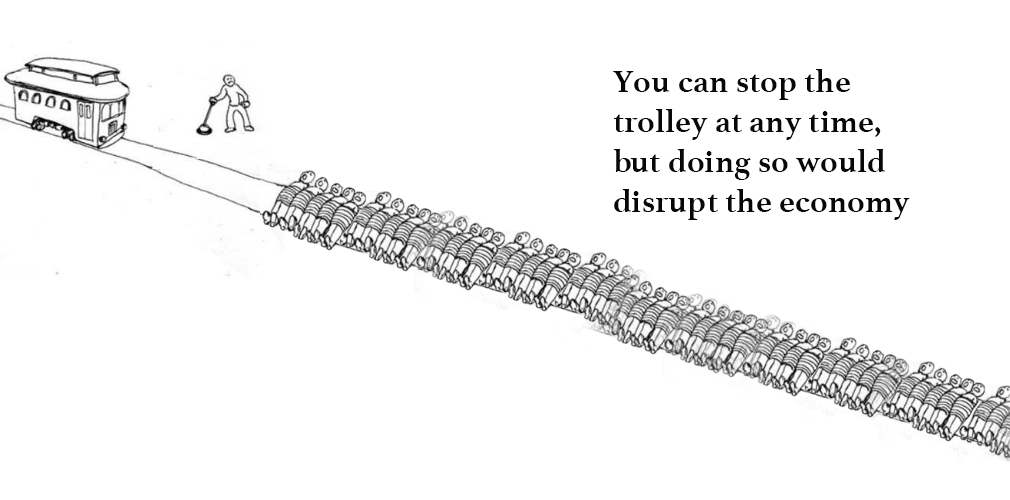

[Featured image is an edited version of the common meme called “The Trolley Problem”]

Written by Lucas Eras Paiva

Archives

Categories

Calendar

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |||

Wow– I found this piece particularly powerful and necessary given our current times. I love how you use the metaphor of the crumbling floor as something that can be seen as hopeful rather than full of despair. I also have been thinking about how this crisis has the potential to reveal the violence and fragility of a lot of our current systems that are failing us at the moment, and I really hope that this idea gains momentum in the coming months rather than fades to the back as those in power continue to prioritize their financial interests. Really well done!

Loved this piece. I thought work-discipline is an interesting concept, and wondered how it relates to other theorists–it predates Foucault, I think, which is cool. Wonder if everyone’s favorite Frenchman was pulling from Thompson when writing Discipline and Punish. I also think bringing the concept of alienation into work under coronavirus is interesting and important. The crisis is making even more obvious the precarity of most American workers; without union-negotiated contracts, most people getting laid off have no assurance of what comes next, and no right to any sort of severance or other benefits from employers. It’s a scary situation, and I was glad to see you contextualize it.