Asthma and Modernity in the South Bronx

Anthropocene . Capitalism . Health & Wellbeing . Personal Reflections . Tales of ProgressModernism makes marks on bodies. Mott Haven and Hunts Point, two of the poorest neighborhoods in the South Bronx, are collectively known as “Asthma Alley” for their high prevalence of asthma. Here, people are hospitalized with asthma at 21 times the rate of some of the city’s wealthier quarters. Despite the area’s low rates of car usage, its residents—95% of whom are non-white—disproportionately bear the burden of the city’s car and truck pollution. Warehouses, like FreshDirect’s massive distribution center, proliferate, sending diesel fumes into the air as goods are trucked towards wealthier neighborhoods. And through it all, cutting across the Bronx like a meat ax, is the Cross-Bronx Expressway, one of the most highly-travelled stretches of road in the country and a pinnacle of modernist thought.

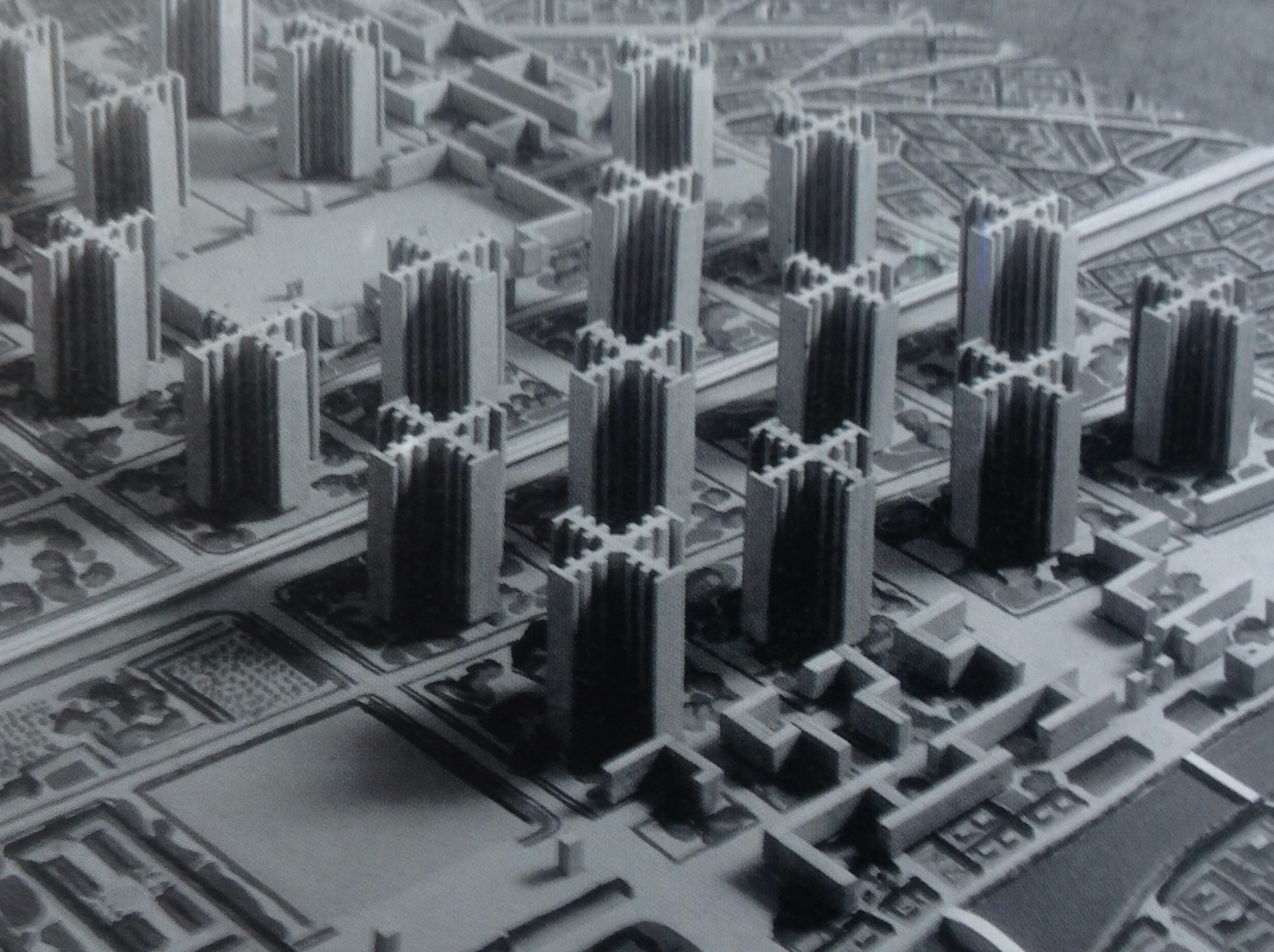

The Cross-Bronx Expressway, like so many other mid-century highways, reflects the modernist turn in urban planning, when European and American architects and city planners started to wonder about what makes a city tick. One influential thinker, Swiss architect and planner Le Corbusier, had come to see crowding, grime, and chaos as endemic to cities. Le Corbusier, concluded that traffic circulation ought to trump everything else: urban ways of urban living which he saw as outdated or unclean could all be fixed if cities were able to get cars moving.

The modernist prescription was simple: cities should no longer be allowed to grow naturally. Natural growth, the critique said, is what led to the sort of disorder Le Corbusier and others believed led to strife in large cities. If cities must grow, these modernists reasoned, it ought to grow as a machine does: ordered, planned, set into motion from on high. The machine city, precisely planned and perfectly scalable, would be the city of the future.

A city is only made scalable by destroying, or at least irrevocably changing, all that came before. The narrow streets of central London, the brownstones and tenements of New York, even the grand boulevards of Paris were seen by modernists like Le Corbusier as obstacles to progress. Human life flourished best not in these places of disordered history, but instead in new sites of ordered modernity: “the streets are at right angles to each other and the mind is liberated,” Le Corbusier once opined. For the modernists, destruction was no problem: the elimination of the old city was not an unfortunate step on the road to progress. Rather, it was progress itself.

Scalability, progress, and modernity itself are inexorably intertwined. As anthropologist Anna Tsing writes, “Progress itself has often been defined by its ability to make projects expand without changing their framing assumptions.” Le Corbusier believed his principles applied as much to a city of ten thousand people as one of ten million. Despite his best efforts to create a scalable city, Le Corbusier never realized his plans to raze central Paris and replace it with towers, or to build geometric cities with triple-stacked streets. But New York had its own modernist builder, one whose four-decade reign oversaw a wholesale reimagining of urban infrastructure, and wholesale destruction of much of the Bronx: Robert Moses.

Moses’ power, beyond the many city and state departments he controlled, was his unique ability to shape New Yorkers’ vision of what modernity looks like. Marshall Berman, a critic of modernism who grew up in the Bronx as the Cross-Bronx Expressway was built, wrote that:

“For forty years, [Moses] was able to pre-empt the vision of the modern. To oppose his bridges, tunnels, expressways, housing developments, power dams, stadia, cultural centers, was—or so it seemed—to oppose history, progress, modernity itself.”

The allure of modernity was inescapable, and, says Berman, “all of us, all Americans, all moderns, were plunging forward on a thrilling but disastrous course.”

The construction of the Cross-Bronx Expressway forever changed the Bronx. Thousands of homes were destroyed, and hundreds of thousands of residents left for greener pastures. Those that were left behind were subjected to increasing states of precarity as businesses fled, opportunity dwindled, and homes were left in disrepair—and perhaps burnt down for insurance money—by landlords. The Bronx of Berman’s youth no longer exists. But, for all the destruction, disinvestment, and change, the Bronx continues to support the countless communities which have risen up since. Today, the South Bronx lives in the shadow of Robert Moses, in the shadow of the Cross-Bronx Expressway, in the shadow of mid-century modernity.

Modernist ideals of scalability, speed, and progress have left their mark not just in the borough’s urban fabric, but in its residents’ lungs; kids in the Bronx are hospitalized with asthma at nearly twice the rate of any other New York City borough, while Bronxites of all ages die of asthma six times as often as the national average. The dream of ever-more people in ever-more cars moving ever-faster proved to be little more than a mirage, something anyone who’s sat in Cross-Bronx traffic can attest to. But the effects on the highway’s victims, effects never thought to be important by its builders, are very much real. Reckless pursuit of modernity has wreaked havoc on the Bronx, and much of its harm cannot be undone. People, nonetheless, find a way to live regardless.

Written by Sam Libberton

Archives

Categories

Calendar

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | |||

Wow, I really love this piece! Aside from it being really eloquently written, I appreciate how you take a very specific example (the Cross-Bronx Expressway) and relate it to larger themes of progress, scalability, and capitalist ruins. I’m impressed by how concise this piece is, and the hyperlinks and images throughout were really helpful and enhanced the overall reading experience. There’s so much to unpack from just a snapshot of a neighborhood and you do a really good job tackling this complexity– I’m now left with a different lens through which I can view my own city and neighborhoods.

Damn, amazing work!! Your work clarified to me how one can effectively apply our in-class content ethnographically. Part of the difficulty of talking about landscapes is to properly escape the confines of abstraction, engaging directly with people’s experiences of their surroundings. Your piece is a perfect example of how to do exactly that!